Between Language and Loss: Reading “The Missing Link” as an Immigrant

Recently, while organizing my writing table and bookshelf after drafting an editorial for the Ashram Bangla website, a collection of short stories, titled The Missing Link caught my eye. I read it some time ago, but as it slipped into my view, I immediately remembered one of its stories, which has relevance to the editorial in which we emphasize the importance of building a bridge between the immigrants and their children who grew up in Canada. As I reflected on the story, I rediscovered how it grappled with unresolved questions of belonging, identity, and the generational gap.

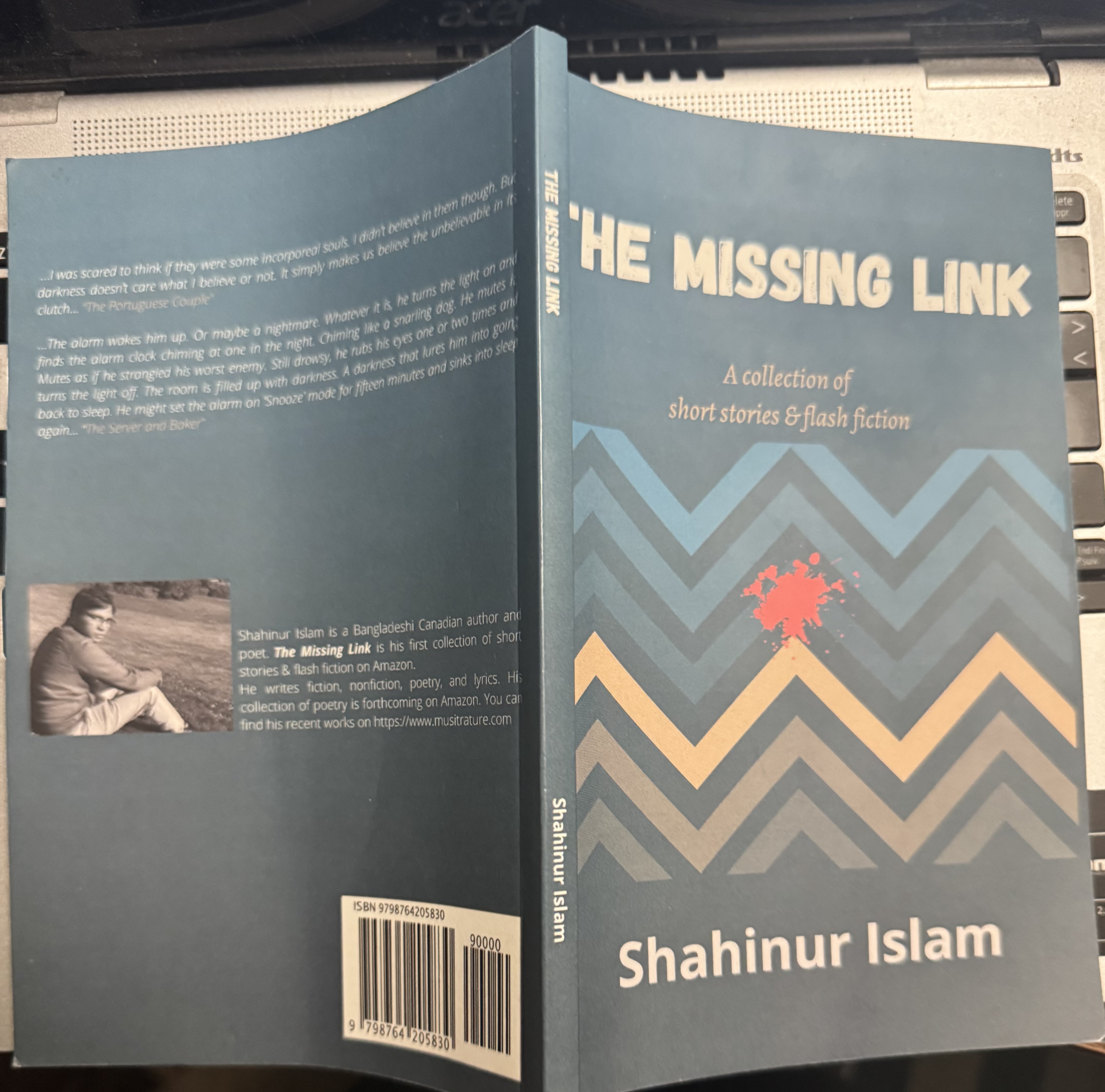

The Missing Link is the first collection of short stories & flash fiction by Shahinur Islam, published by Musitrature on Amazon.ca. Islam is an Ottawa-based Bangladeshi Canadian writer. When I got hold of the book in 2021, I remember reading its every story with interest. I was impressed by the author’s imagination and his use of rhetorical devices. After reading, I planned to write a review, but I relented because of the level of critical engagement it would demand; I was not yet ready to commit to it at that time. So, I just left a brief appreciative review on Amazon.ca.

This time, I decided to take it on. I re-read the title story, whose plot and character I vaguely remembered. But as I was reading it, I found it more interesting than the first time. It gave me many new perspectives about my community in Ottawa, my ongoing conversations with the community, and my own unresolved questions.

The main character of the story, Anik, is a Canadian-born son of a recently deceased immigrant Bengali writer. The father, a respected writer of a local Bangla literary magazine, leaves behind not only his works but also a cultural legacy that Anik is unable to comprehend. The magazine’s special issue, produced to honour his father’s contribution presents a dilemma for him. He is curious about the contents of the magazine, but he can’t read a single word of it, as it is in the Bangla Language that he didn’t learn to read. So, his connection to his father’s literary work becomes more abstract and emotional. This brief paragraph succinctly captures his disappointment:

“Anik was sitting on the chair of their balcony for quite a few hours, staring at the cover page of the magazine in his hand. … he went back to the first page inside the magazine and noticed there were also two words of the same shapes as the cover page, though in smaller shapes than the cover. … he took it for granted that it had been written by the picture. Out of great love and esteem, he touched it profoundly, hugged it tightly, and even kissed it.”

Islam’s narrative restraint is particularly effective here. Rather than moralizing, he allows silence and gesture to carry meaning. Anik’s act of touching, hugging, and kissing the magazine, believing the words inside belong to his father, stands as one of the story’s most affecting moments.

As I read, I found myself thinking less about Anik as a character and more about what he represents. Islam succeeds in articulating one of the most persistent dilemmas faced by immigrant families in Canada and across the West: the gradual disconnection of children from their parents’ language. This is not a new concern. We discuss it among ourselves regularly. We’ve also featured many essays about it in Ashram. However, Islam approaches the issue from a new angle without letting nostalgia interfere with it. Instead, he simply exposes the reality of a loss.

“The Missing Link” addresses a tension that is deeply familiar within Canadian immigrant life. Islam articulates a reality shaped by educational systems and social frameworks that prioritize individual choice and integration over cultural continuity. As he writes: “Many immigrant parents failed to educate their kids in such a manner without their own will as the education and social system here did not allow forcing anything on the kids against their will.” This insight resonates deeply with the immigrant community. In Canada, where the English and French languages dominate public life, parents feel compelled to prioritize integration over inheritance. Teaching Bangla or any languages from their countries of origin can feel like an unnecessary burden in a world already demanding adaptation from children navigating multiple identities. At the beginning I’ve mentioned that “The Missing Link” relates to my editorial for the Ashram Bangla edition, where I’ve highlighted why we haven’t been able to connect with the new generation of Bangladeshi Canadian writers and readers. Their lack of knowledge of the Bangla language and consequent distance from Bangla written culture is a problem of us, not of them. The editorial raises this question that continues to provoke debate: Do we need to teach them our language, which will help them little in the marketplace?

I have wrestled with this question myself. Do we have the right to burden our children with the task of learning a language that offers no practical advantage in their lives? Or should we accept their gradual separation from our cultural heritage that we’ve carried from another country? “The Missing Link” does not answer these questions, but it reframes them. Through Anik’s silent despair, Islam suggests that language is not merely a functional means; it is an expression of the heart; it is the medium through which stories, memories, and affections are transmitted.

What makes Islam’s story particularly compelling is its refusal to moralize. He does not portray the father as a failed parent or the son as a negligent character. Instead, he presents a reality shaped by migration, modernity, and compromise. The loss is collective, not individual. In this way, the story transcends its Bengali context and speaks to immigrant experiences across Canada. It becomes less about specific individuals and more about what is lost when cultural continuity weakens.

I close this reflection not with certainty but with a call to consider the above question more deeply. “The Missing Link” asks immigrants like me to pause and reflect on what we are carrying forward and what we are leaving behind. For that reason alone, Shahinur Islam’s story deserves to be read, not only for pleasure but also for evaluating our ability to hold up to our collective immigrant consciousness.

is the editor of Ashram. He also actively promotes the social and cultural activities of the Bangladeshi community in Ottawa.

No comments yet. Be the first to comment!