Looking Back: BACAOV’s birth, growth, and future - Mustafa Chowdhury

When exactly was the Bangladesh Canada Association of Ottawa Valley (BACAOV) formed? I have asked this question to many Bangladeshi Ottawans. Still, I have not found a satisfactory answer, as none of those in Ottawa at that time could recall the various phases of BACAOV’s formation and subsequent development.

In 1971, there was no separate East Pakistan Association in Canada consisting only of Bengali-speaking East Pakistanis. In the absence of their association and because of linguistic affinity, the Bengali-speaking Indians of West Bengal had often attracted some Bengali-speaking East Pakistanis. The earliest trace of any association consisting of East Pakistani Bengalis in the Ottawa area is the work of Faruk Sarker and his wife, Suzie Sarkar, a year before. Faruk Sarkar was then a graduate student and President of the Pakistan Student Association. In 1970, Faruque started the groundwork for an organization for the Bengali East Pakistani students of Carleton and Ottawa University. Having persuaded them, Faruk and Suzie formed a citizens’ Group for the devastated cyclone victims in East Pakistan. “Are we a part of Pakistan or their serfs or market for their goods only? Is there equal treatment for the Bengalis?” Thus, asked an enraged Sarkar, seeing the total apathy of the West Pakistani rulers. For days, he could not sleep or eat, fearing that all his family members had perished, as there was no trace of his family. “I heard nothing from my family until the end of April. The stubble grew and became a beard. So, in a way, my beard is historic,” recalled Sarkar, who formed an informal coordination committee and exchanged information with the committee’s members in Montreal and Toronto. For the Sarkars (Faruk and his wife Suzie), “it was a never-flagging effort to create a world without exploitation and domination.”

The Sarkars were insistent on naming the Group the Bangladesh Association. In December 1970, the community’s senior members, anticipating military reprisals, did not want to flare up President Yahya Khan’s condescending temper, which, they feared, might result in further military persecution of their family members back home. Despite the Sarkars’ insistence, they preferred to call it something else, certainly not the Bangladesh Association. Thus, historically, what started as a Group in 1970 came to be called the East Pakistan Cultural Association the same year.

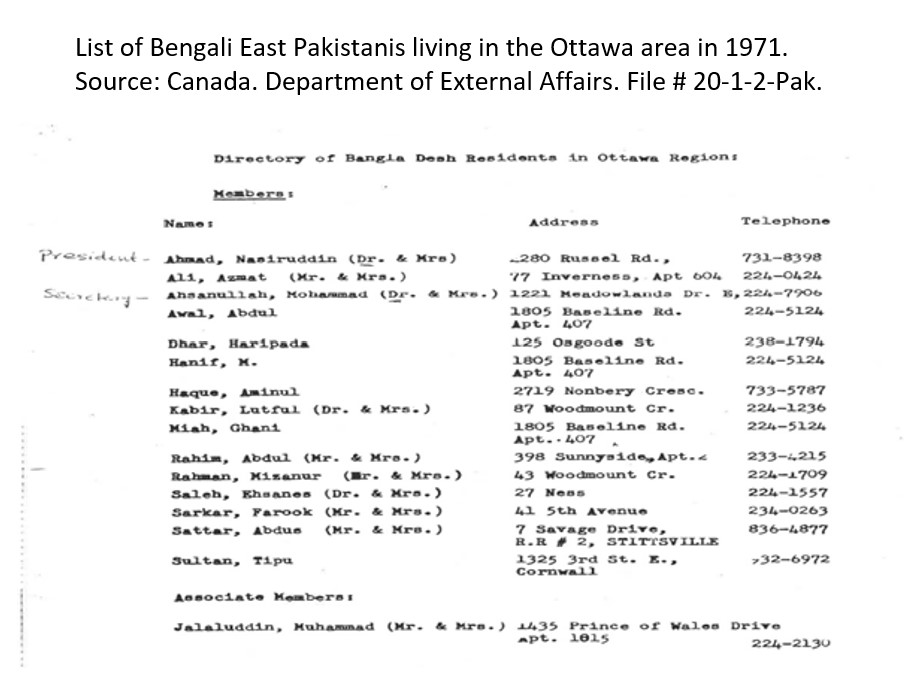

Chronologically speaking, in 1971, Azmat Ali, an IT specialist now living in Washington, D.C., was its first President, while Drs. Luthful Kabir and Mohammad Ahsanullah were its Vice President and Secretary, respectively. Other active members included Drs. Ehsanes Saleh, Mizan Rahman, and Nasir Uddin Ahmed; then Jalaluddin Ahmed, Abdur Rahim, Abdus Sattar, and their spouses; and Tipu Sultan, who lived in Cornwall, also joined the Ottawa group. In addition to Faruque Sarkar, there were a few more active student members, like Haripad Dhar, Abdul Awal, and Mohammad Hanif. Under Sarkar’s stewardship, the group then took up the provocative work of mounting protest demonstrations on the streets of Ottawa.

In late 1970, the East Pakistan Cultural Association’s activities included lobbying the Trudeau administration to aid the victims of tornadoes in East Pakistan. While they were continuing their campaign, the situation turned worse politically with the surreptitious military crackdown on March 25, 1971, on innocent civilians in East Pakistan. Naturally being emotionally disturbed, the outraged members of the East Pakistan Cultural Association began to pressure the government to condemn the Pakistani military dictator.

There is no record indicating exactly how and under what circumstances the East Pakistan Cultural Association became the Bangladesh Association of Canada at a time when it mushroomed across larger cities with the same organizational name with slight variations. Even the most active member, Dr. Mizan Rahman, and others could not recall. However, those directly involved recall it must have taken place immediately after the military takeover. The Bengali-speaking Ottawans immediately changed the organization’s name to the Bangladesh Association of Canada as soon as they dissociated with Pakistan following the secret military crackdown on Bengali civilians. Again, following Bangladesh’s independence, the Ottawa-based Bangladesh Association of Canada changed its name to the Bangladesh Canada Association of Ottawa Valley (BACAOV) in early 1972 to reflect the changing demographic of Bengali Canadians in the National Capital Region (NCR).

Activities of the Ottawa-based Bengali Canadians during the War of Liberation

The initial broadcast to the Canadian public took place on Saturday, 27 March 1971, covering the imposition of martial law through to the declaration of independence of Bangladesh. The Canadians of East and West Pakistani origin took to the streets of major cities such as Toronto, Montreal, Calgary, Saskatoon, and Vancouver. Within days of the military crackdown in East Pakistan, the Bengalis instantly began to refer to East Pakistan as Bangladesh. All Ottawa-based Bangladesh Association of Canada members also began organizing themselves to develop strategies for lobbying the Trudeau administration for recognition of Bangladesh. Though a tiny group consisting of a handful of East Pakistani Bengalis, its members played a pivotal role in 1971 lobbying the Trudeau government. They also undertook activities to raise awareness among Canadians regarding the military reprisals in East Pakistan.

Immediate Public Reaction and Demonstrations

“It transpired that they are among the 20-odd members of the East Pakistan Cultural Association in Ottawa, formed on March 14 with the mailing address c/o Dr. A. B. M. Lutful Kabir, 87 Woodmount Crescent, Ottawa.” Thus, Mitchell Sharp, then Secretary of State for External Affairs, was briefed by John Harrington, Head of the Pacific and South Asia Division of the same Department. “Our immediate reaction was one of shock and disbelief, followed by a spontaneous decision that it was no longer possible to live with the Pakistanis as a single nation. It was, as though, the non-Bengali West Pakistanis turned anti-Bangladeshi and the Bengalis turned anti-Pakistani with a few exceptions.” Thus, Professor Mizan Rahman of Carleton University recalled his own involvement.

The first recorded protest demonstration occurred in Ottawa on 27 March 1971, organized by Professor Nasir Uddin Ahmed of the University of Ottawa. About 30 area demonstrators, mostly Bengali-speaking East Pakistanis, gathered in front of Parliament Hill before marching on to 505 Wilbrod Street in front of the premises of the Pakistan High Commission. Calling President Yahya Khan an “assassin” and a “traitor,” the demonstrators burned a Pakistani flag and a photo of Yahya. They also carried a hurriedly made flag of Bangladesh. Using a battery-operated megaphone, they shouted “Death to Yahya” and “Stop Genocide” and attracted several people despite the cold wintry weather.

On April 2, the Ottawa-based Bangladesh Association of Canada again brought another procession of about 50 people. Like the demonstration of March 27, the same group of people burned the national flag of Pakistan, which, at first, would not work due to the damp weather, even though they tried with a cigarette lighter. After a few tries, the problem was solved “by dipping the flag into the gasoline tank of a nearby parked car.” Thus, Professor Mizan Rahman recalled forty years later. Again, CBC’s Ken Colby reported that the demonstrators condemned the military intervention. Two demonstrators in the front carried an effigy of Yahya, and several demonstrators carried a few banners saying, “Long Live Bangla Desh, my country Bangla Desh,” and “Death to Yahya.” A Canadian daily reported: “Climaxing the Parliament Hill demonstration was a mock trial in which an effigy of Pakistani President Yahya Khan was convicted of crimes against the people of Bangla Desh and hanged.” The demonstrators were also joined by a group from Toronto under the leadership of Schams Ahad to represent the newly formed Bangladesh Association of Canada (Toronto). The National Democratic Party (NDP) MP John Gilbert’s appearance among the protesters encouraged them to believe that Gilbert supported their demand for an independent Bangladesh.

Amidst the crowd, a news reporter suddenly flagged Maqsud Ali, who joined the Ottawa demonstrators to express his misgivings while awaiting admission to the University of Waterloo for the fall session. The reporter asked Ali, “Do you consider this genocide?” “Yes, it is,” thus was Ali’s curt but firm response. The demonstrators then left for the Pakistan High Commission premises. They headed to the embassies of the USSR, China, Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), and Burma (now Myanmar) in the National Capital Region. They demanded an end to the “Yahya Khan’s war” of atrocity against the new state. To many Canadians, the slogans and placards were reminiscent of the Québec Premier Jean Lesage’s era (1960-1966) when the French nationalist party, the Rassemblement pour l’indépendence (RIN), frequently carried placards with the same type of slogans: “Death to the Traitor;” “We want Liberty;” and “Save Our Right.”

Again, on 21 July, a group of pro-Bangladeshi demonstrators carrying placards saying “Long Live Bangla Desh,” “Down with Traitors,” and “Alli-Choudhury Go Back Home” protested outside the National Press Building in downtown Ottawa across the street from Parliament condemning the guests and their supporters. Canadians were already familiar with this type of slogan they heard on television or read in the newspapers since the beginning of the liberation struggle when the protesters from the Young Socialists League carried and waved special placards saying, “Bangla Desh Libre – Québec Libre.” The protesters attracted a few bystanders while the Ottawa police had them all on strict watch as they chanted anti-Pakistani slogans. Inside, Choudhury emphatically denied that “there was a genocidal policy being conducted by the soldiers of Pakistan President Yahya Khan.”

In the early fall, Jalal Uddin Ahmed arranged a meeting of concerned citizens in the Party Hall of his apartment on Prince of Wales Drive. Among the attendees were the Indian high commissioner, Ashok Bhadkamkar, a group of MPs, University professors, senior government officials, and members of the Bengali community.

Jalaluddin’s wife, Shakila Jalaluddin, also significantly mobilized public opinion in favor of an independent Bangladesh in Canada and West Bengal, India. Before arriving in Canada in the late 1960s, Shakila was an MLA attached to the Ministry of Refugee and Relief, Government of West Bengal, India. In late summer, Shakila visited several refugee camps in India. Upon her return to Ottawa, she briefed the community on the dire needs of the refugees. Again, when Abha Maity, former Minister of Refugee and Relief, Government of West Bengal, visited Canada in August, Shakila chaperoned her around and arranged for a community meeting about the ongoing military reprisals in “Occupied Bangladesh.”

When the grisly detail of military reprisals began to filter in, both Azmat Ali and Jahanara Ali of Ottawa remained busy knocking on the neighbours’ doors to get a sense of what they were doing about the army brutality in “Occupied Bangladesh.” The couple was convinced that the Bengalis’ fight for independence had an emotional resonance with the people they had been talking to. Encouraged by their reaction, the couple expanded their network and began sending letters, telegrams, and couriers to local and national political and church leaders. In the ensuing days, the Alis (Azmat and Jahanara) brought along Professor Luthful Kabir and his wife, Bilquis Kabir, who also arranged several rounds of informal meetings with neighbors to raise awareness by encouraging the members to speak their minds and offer comments.

Mizan Rahman recalled how Ottawa’s Bengali-speaking Canadians were committed to raising money for the freedom fighters as soon as they heard about the declaration of independence: “We decided to contribute 5% of our take-home income every month, which we did with no questions asked. There was absolutely no hesitation on the minds of any of us when the collection time used to come at the beginning of every month.” Personally, Masuda Ahsanullah made a trip to India to hand over the money they raised in Ottawa. She recalls handing a cheque directly to Hussein Ali, the first-defected Bengali diplomat in Kolkata, West Bengal, but cannot recall how much they raised. However, she remembers the enthusiastic response from the community. “It was as though the fundraising teams knew how the people of Canada looked upon donation at the time they were approached - giving whatever one could to help a refugee in dire need in India,” recalled Azmat Ali and Jahanara Ali.

Bangladesh Association of Ottawa worked closely with NGOs all through 1971. Larry Tubman, OXFAM Canada’s Assistant Director, for example, wrote to Professor Mizan Rahman, General Secretary of the Ottawa-based Bangladesh Association of Canada in the following: “Oxfam is most grateful to you and your fellow members of the Bangla Desh Association of Canada for your generous support of our efforts on behalf of the refugees for the East Pakistan crisis and looks forward to meriting your continued assistance.”

Awareness Raising

The Bengali Ottawans spent much time raising awareness among the Canadian public through sensitization. The written materials they prepared for fundraising did not need to look slick and high-powered. Still, they needed to look pleasant and easily read, catching readers’ immediate attention in the first second or two and blocking out the distractions. At its heart, it was one individual giving another, observed Ali. They made every effort to combine words and pictures skillfully weaving into the story of military reprisals on unarmed civilians that would hold the Canadian public spellbound and inspired. “It was a challenge to remain consistent and yet engage the public at an emotional level to ensure that no one went overboard;’’ and that “they all sang from the same song sheet,” recalled Professor Lutful Kabir of Carleton University and his wife, Bilquis Kabir.

Again, individually active among the Ottawa Bengalis was M. Abdur Rahim, who was outraged to see a caption he could not recall in which paper, “You have to be a Bengali to be shot at.” He immediately dashed off the following telegram to Leonid Brezhnev, General Secretary of the Central Committee (CC) of the Communist Party of the USSR: “Tell Yahya to stop the carnage.” The ongoing reports of the killing of the Bengalis evoked in Rahim’s mind the haunting memories of the Nigerian civil war of 1967-1970, recalled an enraged Rahim. He also immediately initiated a petition and collected many signatures. In September 1971, before moving to Hamilton, Rahim left a draft copy of his petition, which he had crafted after spending hours at the local downtown Public Library with Professor Nasir Uddin Ahmed, then President of the Bangladesh-Canada Association (Ottawa). Ahmed took over the unfinished work and, with help from a few volunteers, had the petition signed by several professors of both Carleton and Ottawa University and sent the petition to the UN Secretary-General.

Campaign for Recognition of Bangladesh

Throughout nine long months, Bengali Ottawans continued to lobby the government to recognize Bangladesh as soon as possible. They networked with other Bangladeshi Associations and worked jointly to keep the Trudeau administration under pressure. They met senior Ottawa officials on numerous occasions demanding that Canada consider recognizing Bangladesh even though they were aware of Canada’s position regarding the Bangladesh issues. They knew that Canada had its foreign policy constraints and were fearful of the reaction of the people of Quebec, who were demanding a sovereign Quebec devoid of Canada. This was unacceptable to the Trudeau administration, which had to struggle hard not to provoke separatists in Quebec. The Bengalis were also aware of Canada’s limitations as a Middle Power being an ally of the USA at a time when the Nixon administration was supportive of the Pakistani military dictator.

With such knowledge in mind, Bengali Canadians approached the Trudeau administration with caution but firm determination to show no nexus between the situation in Quebec and Bangladesh. The circumstances are different, so there is no fear of provocation. This was the key message Bengalis wanted to put across to the Trudeau administration. In a sense, they convinced government officials who were still hesitant to take an open [position in favor of Bangladesh.

Nevertheless, on December 17, 1971, the day after the liberation of Bangladesh, Bengali Ottawans took a different approach since Bangladesh had already become independent and that, ideally, Canada should have no foreign policy constraints. With such thought and justification, Canada would have no foreign policy constraints. Unsurprisingly, therefore, Ottawa received a letter from a group of pro-Bangladeshis. “The birth of the new nation of Bangla Desh is now a reality. The Pakistani Army in Bangla Desh has unconditionally surrendered…. The government of Bangla Desh is in effective control of the entire territory of East Bengal and enjoys the full support of its people. WE, THEREFORE, URGE YOU TO RECOGNISE THE GOVERNMENT OF BANGLA DESH AND THEREBY ESTABLISH A LASTING FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE PEOPLES OF CANADA AND BANGLA DESH.” Speaking on behalf of the jubilant Canadians of Bangladeshi origin, A. B. Sattar, Executive Secretary, Bangladesh Association of Canada (Ottawa), appealed: “One way that Canada can help Bengalis strengthen their new nation is to recognize its de facto presence in the world community. We urge the Government of Canada to demonstrate this country’s farsightedness and pragmatism again by recognizing the national status of Bangla Desh. … The people of East Bengal are now citizens of an independent nation, free to govern themselves and free from exploitation and oppression. … 75 million Bengalis will assure its permanence.” It was Sattar’s grand hope that Canada would help establish a lasting friendship between the two countries.

Though a small group, it is incredible to note the extent to which Bengali Canadians in the Ottawa area continued their work in support of Bangladesh. They played a significant role, just like the members of the Bangladesh Canada Association of other major Canadian cities. We must recognize their work and continue to honor the organization involved in demanding the recognition of Bangladesh when there was no certainty that there would be a free and sovereign Bangladesh.

Between 1971 and 2024 - that’s an extended period. Like any other organization, BACAOV had a chequered life, going through troubled times and surviving. BACAOV was under the stewardship of the following: Azmat Ali, Professor Mizan Rahman, Professor Nasir Uddin Ahmed, Dr. Muhammad Ahsanullah, Dr. Maksudur Rahman, Nazmul Hossain, Rasheda Nawaz, Faruq Faisel, Shahiduzzaman Jewel, Enayetur Rahman, Shah Bahauddin Shishir, Syed Serajul Islam Khokon. For years, BACAOV was dormant. Many community members were disappointed and discouraged. Only when Shah Bahauddin Shishir took over in 2018 did BACAOV rejuvenate and undertake several activities. Bahauddin Shishir and his wife, Nasreen Shoshi, and their team are to be commended for their initiatives and hard work. Community members were happy to see BACOV’s rebirth.

Again, many volunteers and their spouses remained dedicated and spent hours reviving BACAOV over the years. As we look back, we may recall with gratitude the names of the following volunteers: Kabir Chowdhury, Mohsin Bakht, Sultana Shirin Shazi, Gul Jahan Rumi, Sheikh Farque, Ashiq Biswas, Reaz Zaman, Zahida Begum, Golam Rabbani Mitu, Enamur Rahman, Sailesh Deb, Syed Faruk Anwar Mintu, Mohammed Anwar Hossain, and many others whose name I can’t recall. If any of you are missed here, please pardon me for that.

Today, in December 22024, unfortunately, there is an alarming fact about BACAOV - there are too many chiefs and not many Indians. I recently learned about the conflict between BACAOV’s Executive Committee and the Advisory Members. Emotions have reached new heights of intensity, and both groups are at loggerheads. My heart quails as I write this piece, for I was BACOV’s General Secretary for two years from 1985-1987. We worked tirelessly to enable BACAOV to grow. It is hard to bear the piercing pathos of the situation. Naturally, Bangladeshi Ottawans feel a profound sense of dissatisfaction and a general feeling of disillusion.

I see BACAOV as a platform for us through which community members come together to build valuable connections. BACAOV has played an essential role in exposing Bangladesh’s culture, traditions, and history to our children and grandchildren, enabling us to unite around a common cause by fostering a sense of belonging and shared purpose.

My appeal to you all: “Let’s unite under a familiar slogan to foster growth and collaboration among ourselves for greater interest.” Read the BAVAOV’s constitution – see what it says and how you may resolve the disagreements best.

Long Live BACAOV!

NOTES & REFERENCES

Email from Faruk Sarkar to Mustafa Chowdhury, dated May 1, 2012. Sarkar was a graduate student at the University of Ottawa at the time. The author has known Sarkar and his wife, Suzie Sarkar, since the 1970s. The Faruks now live in Ottawa.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Canada. Department of External Affairs. Restricted Letter from Head of Pacific South Asia Division to from GPS to PDM. Dated, March 29, 1971. File # 20-E -Pak-1-4.

Email from Professor Mizan Rahman to Mustafa Chowdhury, dated March 8, 2011. Dr. Rahman has lived in Ottawa throughout his career. The author had numerous opportunities to discuss his involvement in various activities supporting Bangladesh with Professor Rahman.

Email from Professor Mizan Rahman to Mustafa Chowdhury, Op. cit.

Kitchener-Waterloo Record, dated April 13, 1971.

Email from Dr. Mir Maqsud Ali, Professor Emeritus, the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, to Mustafa Chowdhury, dated May 15, 2017. The author followed up with him and interviewed him three times in 2017. The author has known Ali since the 1960s.

The Making of the October Crisis: Canada’s Long Nightmare of Terrorism at the Hands of the FLQ. Doubleday Canada. Montreal. 2018. p. 13.

The Globe and Mail, dated July 22, 1971.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Jalaluddin Ahmed stated this to the author during his August 14, 2005, interview in Ottawa. The author also interviewed Shakila Jalaluddin. Professor Lutful Kabir was also present with the author, who had known them for a long time. The author spoke with the Ahmeds on many occasions.

Ibid.

Email from Professor Mizan Rahman to Mustafa Chowdhury, March 8, 2011. Op. cit.

The couple lived in Ottawa for several years and then moved to the States in the late 1980s. The author met them several times. Specifically, the author interviewed Dr. Mohammad Ahsanullah and his wife, Masuda Ahsanullah, on March 22, 2011. They confirmed the summary of their input in a letter to Mustafa Chowdhury dated May 6, 2011. The author then followed up over the telephone.

The author interviewed Azmat Ali and Jahanara Ali, who live in Washington, D.C., on January 11, 2008. The couple then confirmed the summary of the interview in an e-mail to Mustafa Chowdhury dated March 10, 2008. Since then, the author has regularly contacted Azmat Ali and received more input, especially regarding awareness-raising in the Ottawa area.

Letter from Larry R. Tubman, Assistant Director, OXFAM Canada, to Dr. M.M. Rahman, General Secretary, Bangladesh Association of Canada, dated November 12, 1971. MG 28 I 270 Volume 18 File: Pakistan Ref General. Library and Archives Canada. Op. cit.

See footnote 17.

Professor Lutful Kabir of Carleton University observed this in his interview with the author on May 12, 2005, in Ottawa. Since the author and the couple live in the same city, the author talked to the couple numerous times, both formally and informally, to gather as much information as possible. The Kabirs were active in 1971 from the very beginning of the military assault in Pakistan. Dr. Kabir confirmed the information he had provided over the years in a separate email dated July 10, 2011, to the author.

Abdur Rahim narrated this to the author on July 5, 1997, in Ottawa. Following that, Rahim confirmed the same information in writing in a letter dated August 2, 1997. Since Rahim lived in Ottawa, the author had numerous opportunities to meet with him to discuss the unforgettable days of 1971 in Canada and Canada’s awkward position regarding the conflict.

This is a one-page letter of appeal addressed as Dear Sir, by A. B. Sattar, Executive Secretary, Bangladesh Association of Canada, Ottawa, dated December 17, 1971. The letter was hand-delivered to all MPs and a few selected Department of External Affairs officials. This may be found in Andrew Brewin’s Papers in the Archives under Pak Bangladesh correspondence. Volume 87. File # 87-13. MG 32 C26. Library and Archives Canada. Op. cit.

This was added as a separate note from the Bangladesh Association of Ottawa, dated December 21, 1971. Ibid.

Mustafa Chowdhury

Ottawa, Canada

email: mustafa.chowdhury49@gmail.com

December 15, 2024

PS:

Some of the materials in this article are from the author’s recently published book Birth of Bangladesh as Canada Walks a Diplomatic Tightrope, published by Xlibris, Indiana, USA, 2024. If you want to procure a copy, don’t hesitate to contact the author directly.

-

en-ashram-N/G

-

25-12-2024

-

-